Edited by People Management Competence Centre & Lab

“The world is looking to Norway”, this is what an Italian newspapers announced in 2011 (La Repubblica, 2011). Indeed, Norway was the first country to introduce a law regulating gender balance on corporate boards. Ambitions about achieving gender balance in the upper echelons of Norwegian companies had existed for a long time. “However, any advances in increasing the number of women on corporate boards had little visible effects. In 1992, only 4 percent of the members of boards in corporations listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange were women, and in 2002 this figure had increased to only 6 percent despite efforts made” (Machold, Huse, Hansen, and Brogi, 2013 p. 1). This was the background for the Norwegian law on gender balance in corporate boards, and in 2008 about 40 percent of the board members in Norwegian publicly traded companies were women. The snowball starting in Norway is growing, and the effects seem to be accelerating, leading one country after another to follow the Norwegian example (Machold, Huse, Hansen, and Brogi, 2013). The most important lesson to be learnt from Norway is that even in a country where a gender-balance attention is well established, it was necessary to introduce a law in order to make significant increases in the number of women on boards. In Italy, the turning point came with the introduction of the Law 120/2011, the so called Golfo-Mosca Law (from the name of the promoters). The Law requires that boards (executives and non-executives) of publicly-listed companies and state-owned companies have at least 33% of female by 2015 and sets a target of 20% for the transition period.

Four years after the law, the question we ask is this: does the increasing number of women on corporate boards improve organizational performance?

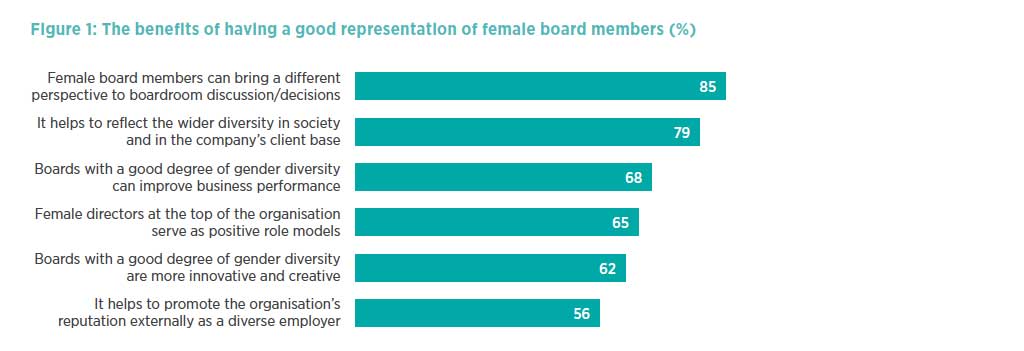

According to several studies carried out by research institutes and consulting firms, most HR managers and HR professionals believe that having a good gender balance on boards conveys several key benefits to the organization, such as bringing different perspectives to decision-making, reflecting the wider diversity in society, etc. (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1: CIPD Report 2015

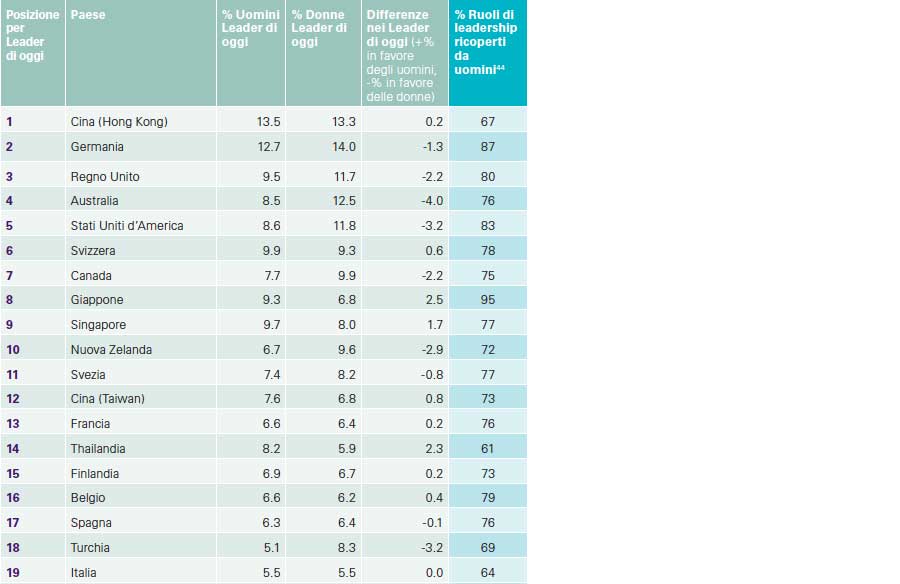

Moreover, according to CEB SHL Talent Report 2013, the difference in the leadership potential of women and men is less than 1% in favour of women. This means that the pool of female potential leaders is not smaller as compared to the male pool. However, more than 60 percent of leadership positions are filled by men (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: Leadership Potential – broken down by gender – Source: CEB – The 2012 Talent Report

The effects of diversity (age, gender, cultural, ethnical) on individual, group, and organisational performance have been widely investigated also in management literature and evidences are highly interesting.

Some scholars solicited a reflection on potential negative effects of diversity in terms of conflict worsening, poor communication, and a reduction of group cohesion. On the other side, some scholars showed how diversity may increase creativity, innovation, decision making and, hence, performance. A recent study produced at St. Gallen University on a large sample of banks showed a positive and strong relation between gender diversity and perfomance, over 15 years. According to Reinert et al. (2015) women’s contribution to firm’s performance appears to be particularly valuable in times of crisis: they found that a 10% increase in the number of women in top management positions produced an increase on ROE greater than 3% per year, and this impact doubled in the years of severe crisis.

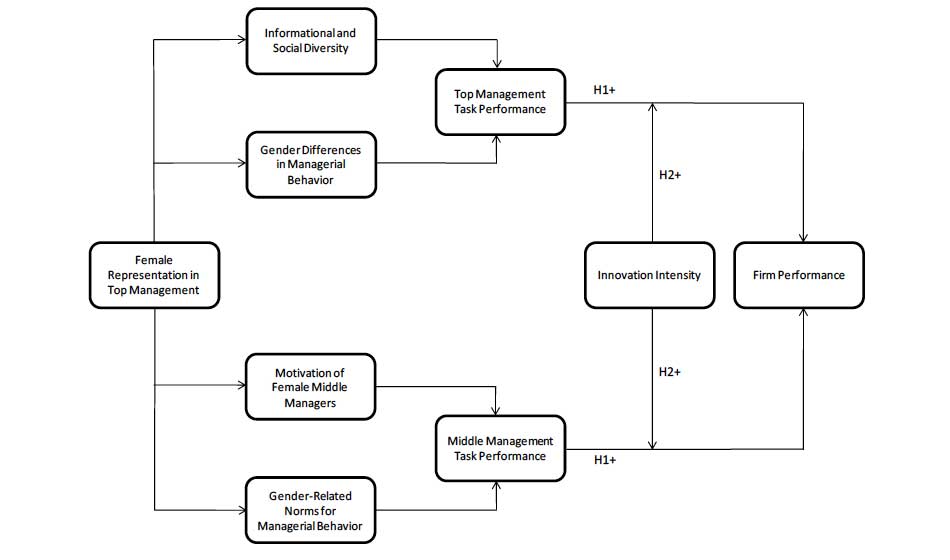

There is another important study, published in 2012, which helps in understanding the rational of this positive relationship (Dezső & Ross, 2012). According to the results of this research carried out on 1,500 companies over a period of 15 years, the presence of female top managers increases the performance of (both top and middle) management, and by this means also firm’s performance. Women, indeed, thanks to their different life experiences, contribute to management team with additional insights on some strategic issues, and in particular those on female business partners, customers, employees.

More generally, heterogeneous groups benefit from different views, consider a wider set of possible solutions, debate the views of others with greater force, thus leading to higher quality decisions, especially when (as for decisions by top management teams) the task requires to analyze and process lots of information. It is true that diversity can also reduce social cohesion, engender conflicts, and reduced comfort within the group, but not necessarily this may result in a lower performance; on the contrary, it may generate better decisions, especially when they are “non-routine decisions”, as in the case of Board ones. In those cases, benefits from gender diversity seem to outweigh its costs.

Moreover, according to this study, the positive impact of women in the Top Management Team is not limited to the performance of the team but is extended to other levels of the organization. At some stages of career progression, in fact, mentoring relationships and other supportive relationships can be very important; since these social relations are strongly influenced by the similarity on certain social factors such as gender, the scarcity of women in top management can become a barrier to career opportunities for women. On the contrary, women in positions of senior management seem to be more sensitive than their men colleagues to growth of their employees, encouraging them to express their full potential. Therefore a woman should strongly believe that the presence of other women colleagues in senior management roles can increase her real career opportunities; this condition can positively affect motivation and commitment of women at all organizational levels.

Finally, the results of this research show that the benefits of gender diversity in top management team are visible only in certain contexts, namely in those tasks that require creative solutions, such as in innovative processes based on the recombination of unique resources and competences. As a consequence the women presence on boards would be particularly important in those companies where innovation represents a key component of the strategy and, then, of managerial behaviours (Figure 3).

Fig. 3 – Source : Dezső & Ross, 2012

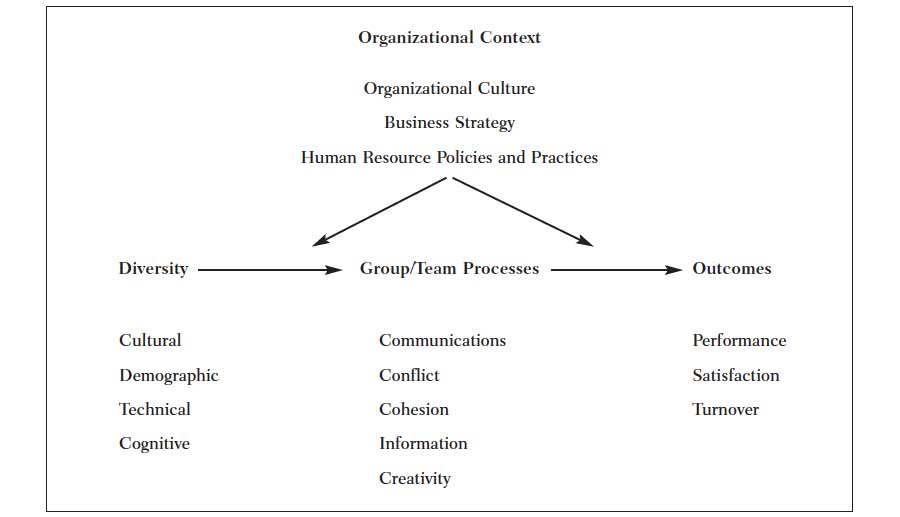

According to these considerations, perhaps there isn’t a single answer to the question that we asked ourselves, as more and more evidences lead us to believe that the impact of diversity on performance depends on some contextual factors such as organizational culture and strategy, and HRM practices adopted (Figure 4).

For example, the impact of diversity on performance will be positive when managers and their collaborators, are able to rely on the creativity and wealth of information; when they are coached, through cultural awareness and adequate HRM practices to deal with the complexity related to taking decisions or communicate in a very heterogeneous team. If this is true, then we have to accept – in a managerial perspective – the fact that gender diversity creates value if there are some contextual factors, that are able to take out its potential.

And since diversity is a feature of the labor market and a social value, then companies have to gear up to create an inclusive organizational culture, and develop the skills needed to generate value from diversity.

Figure 4: Diversity effects on performance Source: Kochan et al. 2003

Surely, having set percentages of women participation on Boards represents a key step, since it helps in creating an open and supportive culture, triggering a cascade effect that, over time, will ingender benefits on all organizational levels.

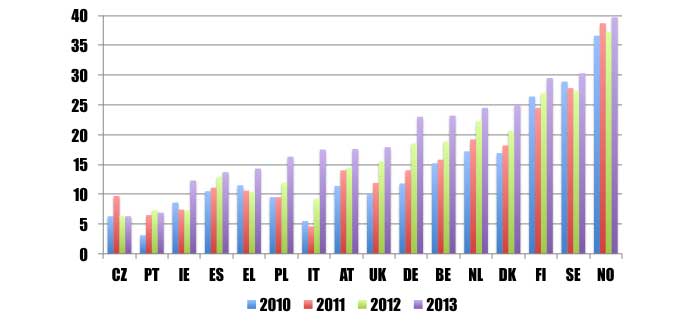

Four years after the introduction of law on installments to women participation on Boards data shows that even in Italy, the effect has been high and the number of women on Boards has significantly increased (Fig. 5). However to generate a real impact, top management must ensure a visible commitment.

Moreover, as it is true that “you can not manage what you do not measure,” it is extremely important to adopt a more analytical approach on this issue and collect and analyze corporate data, monitor gender profile, and ensure greater transparency on these data. Finally, it is important to adopt policies to support gender diversity in the recruitment and selection process, in the design of career and in the adoption of work-life balance initiatives.

Fig.5: Women on Corporate Boards (%) – Source: Credit Suisse, 2014

References

- Burke Eugene et al. “Big Data Insight e Analisi della forza lavoro globale”, The SHL Talent Report, 2014.

- CIPD, “Gender diversity in the boardroom: Reach for the top”, Survey Report, Feb. 2015.

- Dezsö, Cristian L., and David Gaddis Ross. “Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation.” Strategic Management Journal9 (2012): 1072-1089.

- Kochan, Thomas, et al. “The effects of diversity on business performance: Report of the diversity research network.” Human Resource Management1 (2003): 3-21.

- Machold, Silke, et al., (eds). “Getting women on to corporate boards: A snowball starting in Norway”. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2013.

- Reinert, Regina M. et al. “Does female management influence firm performance? Evidence from Luxembourg banks”, Working Papers on Finance n. 2015/1, Swiss Institute of Banking and Finance (S/BF – HSG), Jan. 2015.

25 January 2016